CREATIVE VOICES

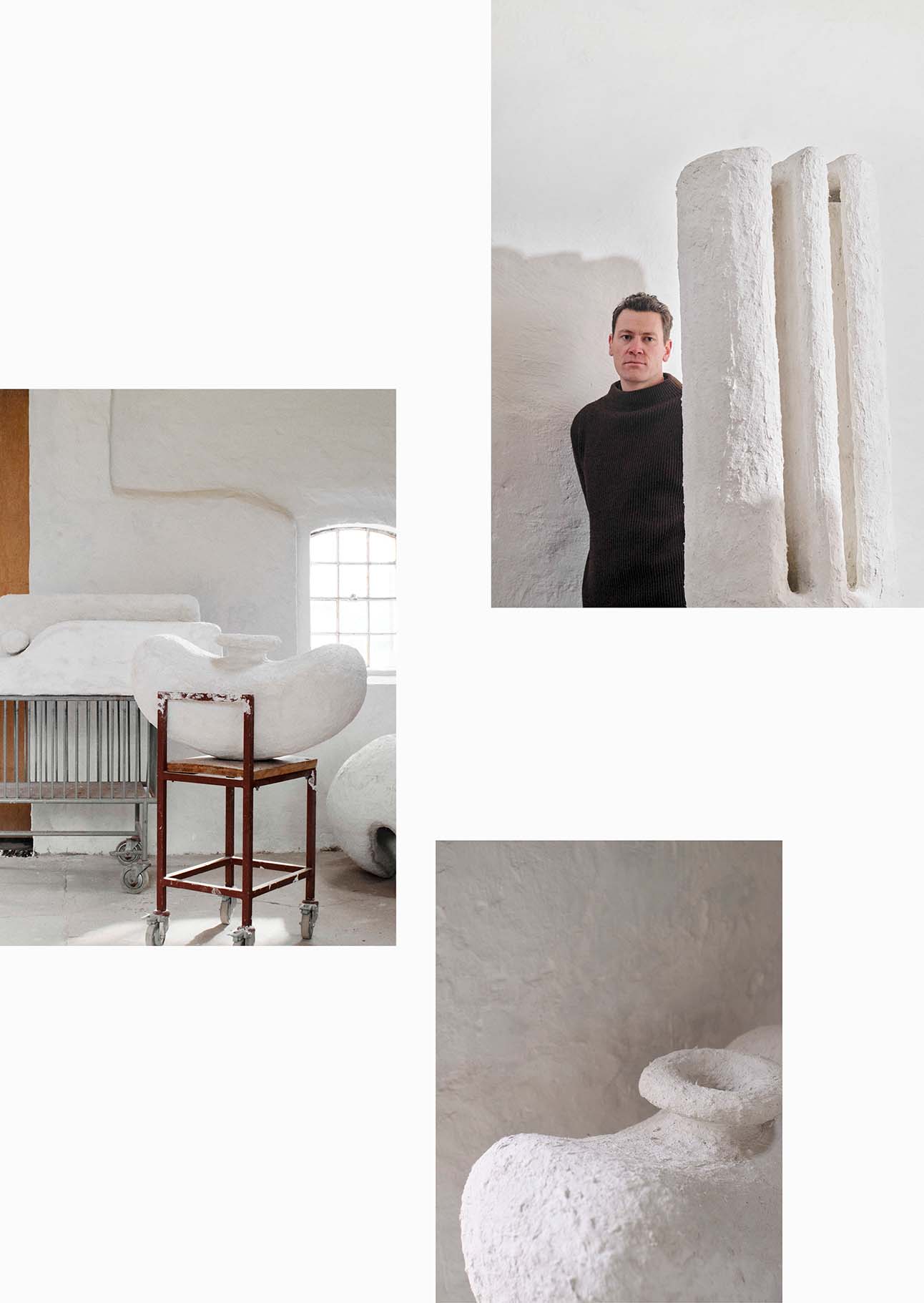

— CARL EMIL JACOBSEN

Design

The landscape surrounding Carl Emil Jacobsen provides the materials and colours that form his sculptures, reminiscent of ancient forms and archaeology.

Perched in the unusually elevated terrain of Søhøjlandet, in otherwise level Denmark, sits sculptor Carl Emil Jacobsen’ studio, part of an old farmhouse, filled with rounded sculptures in earthy and rich shades of red, terracotta and rust. These saturated hues originate in the subdued landscape right outside, in the intersection between man and nature, as Jacobsen makes his own pigments from chalk, clay, minerals, rocks and reclaimed brick from the region. “I have never been able to let go of the landscape I grew up in and I use it actively, gathering earth, rocks and sand to grind into materials for my work. That kind of two-sided connectedness is crucial to me, to be based in a place which I know intimately, which I also utilise as a material or medium in my practice.” Formally trained as an industrial designer, he leans towards an experimental and material-driven process where ancient forms and principles meet industrial processes. His obsession with archaeology as a child is something that still echoes through his work, often as a scaling-up of certain archaic objects, mechanisms and shapes, such as the blade, pipe or trough, inflated from the dimensions of the hand-held to the architectural. Encountering his sculptures, viewers use their body to make sense of the object, moving around, crouching to look inside; they demand interaction. The textured surfaces of the work enforce this magnetic effect, vivid and tactile, often made from natural materials or repurposed brick ground in a mill manufactured by Jacobsen. Developing these started with a profound frustration with the uniformity and plasticity of industrially made acrylic colour. One particular deep-burgundy-hued sculpture is emblematic of this rebellion: “While replacing a floor in a very old house, my friends excavated the original fireplace which had been dug down for years. I extracted these incredible dark red bricks from there, probably a result of being warmed up and cooled down so many times, mixing with soot. Only salvaging a couple of bricks, I am almost out of it. As every pigment I make is unique, I can never mix it again the exact same way. This giving up of control is quite interesting to me.”

This story appears in Ark Journal VOL VI.

STYLING PERNILLE VEST

PHOTOGRAPHY ANDERS SCHØNNEMANN

WORDS ALISA LARSEN

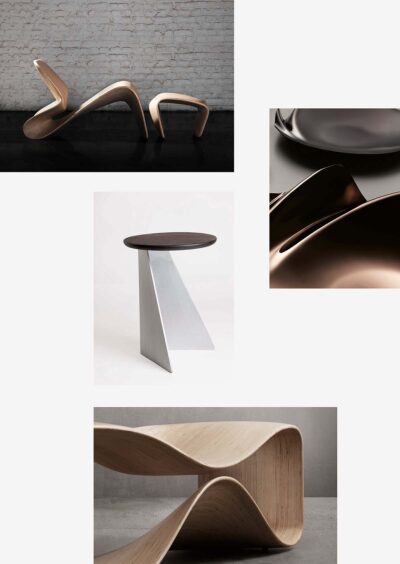

CASE STUDY

— DISSONANT BEAUTY

As in music, interior design calls on many elements – rhythm, contrast, repetition – to create that most subjective of visions: beauty.

DESIGN MUMBAI

India’s creativity, natural resources, extensive skills, technological advancements and deep historical roots deserve wider recognition and appreciation.

CINCINATTI MODERN

High on a hillside in Cincinnati, sits a two-storey modernist wonder by two unsung heroes of American architecture, built for an art collector in the 1980s and that has been given a sensitive makeover to accommodate the collection of its second owner.

CREATIVE VOICES

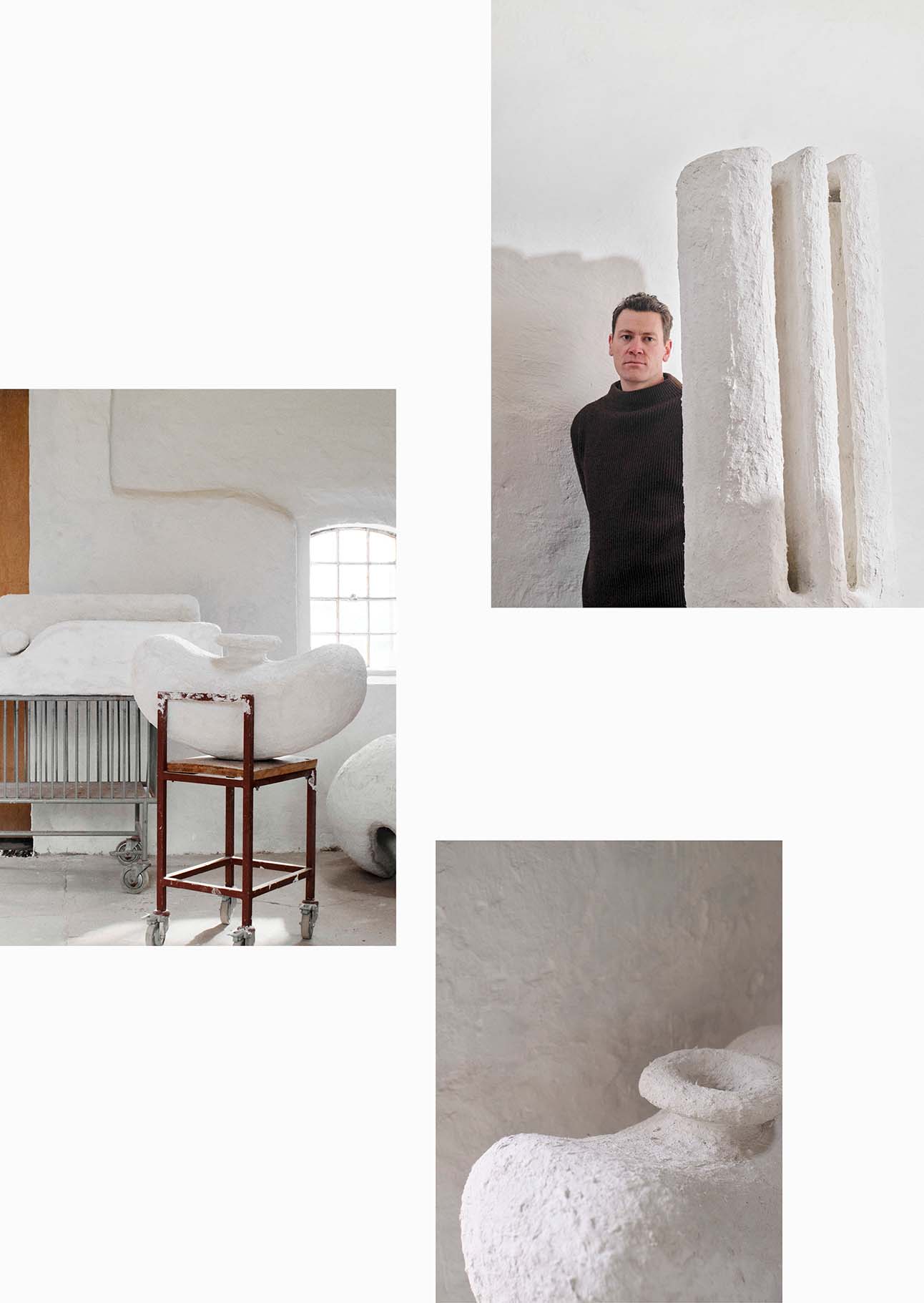

— CARL EMIL JACOBSEN

DESIGN

The landscape surrounding Carl Emil Jacobsen provides the materials and colours that form his sculptures, reminiscent of ancient forms and archaeology.

Perched in the unusually elevated terrain of Søhøjlandet, in otherwise level Denmark, sits sculptor Carl Emil Jacobsen’ studio, part of an old farmhouse, filled with rounded sculptures in earthy and rich shades of red, terracotta and rust. These saturated hues originate in the subdued landscape right outside, in the intersection between man and nature, as Jacobsen makes his own pigments from chalk, clay, minerals, rocks and reclaimed brick from the region. “I have never been able to let go of the landscape I grew up in and I use it actively, gathering earth, rocks and sand to grind into materials for my work. That kind of two-sided connectedness is crucial to me, to be based in a place which I know intimately, which I also utilise as a material or medium in my practice.” Formally trained as an industrial designer, he leans towards an experimental and material-driven process where ancient forms and principles meet industrial processes. His obsession with archaeology as a child is something that still echoes through his work, often as a scaling-up of certain archaic objects, mechanisms and shapes, such as the blade, pipe or trough, inflated from the dimensions of the hand-held to the architectural. Encountering his sculptures, viewers use their body to make sense of the object, moving around, crouching to look inside; they demand interaction. The textured surfaces of the work enforce this magnetic effect, vivid and tactile, often made from natural materials or repurposed brick ground in a mill manufactured by Jacobsen. Developing these started with a profound frustration with the uniformity and plasticity of industrially made acrylic colour. One particular deep-burgundy-hued sculpture is emblematic of this rebellion: “While replacing a floor in a very old house, my friends excavated the original fireplace which had been dug down for years. I extracted these incredible dark red bricks from there, probably a result of being warmed up and cooled down so many times, mixing with soot. Only salvaging a couple of bricks, I am almost out of it. As every pigment I make is unique, I can never mix it again the exact same way. This giving up of control is quite interesting to me.”

This story appears in Ark Journal VOL VI.

STYLING PERNILLE VEST

PHOTOGRAPHY ANDERS SCHØNNEMANN

WORDS ALISA LARSEN